How form beats substance in financial markets

By Resco Advisory Board Member Kevin Corrigan

Originally told in James Surowiecki’s book The Wisdom of Crowds and lately by John Kay in Other People’s Money, the parable of the ox tells the tale of a “guess the weight” competition. Participants aim to guess the weight of the ox and such is the interest in this that no one remembers to feed the ox and it dies. As a parable for the futility of modern financial markets it is humbling. Our obsessions with the form and not the substance of what we do can often lead to poor outcomes. Similarly, how we judge and are judged is central to modern investing and yet we persist with some very odd ways of demonstrating this. Benchmarks are the most accepted point of validation for many investors. For pension funds, they can represent a funding objective while for retail investors they are a proxy for the market or peer performance. Investors naturally look to benchmarks as the white lines on the playing field, the arbiters of success. But in these enlightened times when value for money, quality and social good are often as important as financial return, are traditional benchmarks fit for purpose? Have we forgotten about the ox?

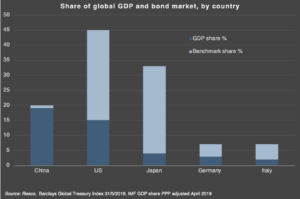

At a basic level, a rules-based methodology means most benchmarks for liquid markets, whether equities or bonds, are easily understood. An important advantage. But their flaws are real: misallocation of capital; lack of fundamental value; concentration risk; momentum behaviour and distortion; conflicts of interest and stewardship; and limitations on divergence. Benchmarks have created more problems than they have solved, hence why passive assets in the US represent just 15% of the total US equity market capitalisation, despite the growth in low-cost solutions or cheap ‘beta.’ In bond markets, following a benchmark is tantamount to benign neglect. The biggest borrowers get the biggest weight. Any bank manager building a loan book based on which customers asked for the most money would be derided, yet this is the accepted practice in traditional fixed income investing.

At a basic level, a rules-based methodology means most benchmarks for liquid markets, whether equities or bonds, are easily understood. An important advantage. But their flaws are real: misallocation of capital; lack of fundamental value; concentration risk; momentum behaviour and distortion; conflicts of interest and stewardship; and limitations on divergence. Benchmarks have created more problems than they have solved, hence why passive assets in the US represent just 15% of the total US equity market capitalisation, despite the growth in low-cost solutions or cheap ‘beta.’ In bond markets, following a benchmark is tantamount to benign neglect. The biggest borrowers get the biggest weight. Any bank manager building a loan book based on which customers asked for the most money would be derided, yet this is the accepted practice in traditional fixed income investing.

Another challenge in traditional benchmarking is the distortion in liquidity that can result. Take for example small cap stocks in the US. Entering the holy grail that is the Russell 2000 can often improve the investability of a company’s shares and potentially the number of analysts covering the stock. If you are on the wrong side of the white line and not included, does that represent an acceptable distortion? Passive rebalancing, whereby funds buy and sell stocks to rebalance to an index, is also having distorting effects. Since 2005, 16% of the trading volume in US stocks has occurred in the last half hour of the trading day¹.

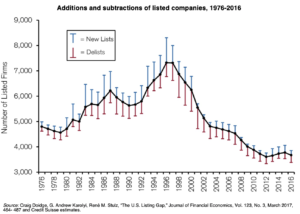

Perhaps the most telling critique of benchmarks is the misallocation of capital that results from these distortions – the very antithesis of what efficient capitalism should be. In bond indices it is manifest in lending to the most indebted rather than the most creditworthy borrowers. In equity markets it fuels concentrated industries and individual companies. Credit Suisse researchers pointed out that in 1996 there were 7,322 listed companies in the US compared to 3,671 by the end of 2016 – a drop of 50%².

Perhaps the most telling critique of benchmarks is the misallocation of capital that results from these distortions – the very antithesis of what efficient capitalism should be. In bond indices it is manifest in lending to the most indebted rather than the most creditworthy borrowers. In equity markets it fuels concentrated industries and individual companies. Credit Suisse researchers pointed out that in 1996 there were 7,322 listed companies in the US compared to 3,671 by the end of 2016 – a drop of 50%².

The 2019 Equity Gilt Study by Barclays also confirms the sharp increase in market concentration since the turn of the last century. But why is this? There are a number of reasons. Large companies that receive large index weights have arguably benefitted from globalisation at the expense of smaller companies. Competition, the very lifeblood of capitalism, has been choked. Mergers and acquisitions and new tech entrants have also had an impact. The protracted recovery since the GFC and low interest rates have fostered increased buybacks at the expense of investment. This goes hand in hand with a decline in productivity where larger, more concentrated companies and industries need less investment to sustain their already significant market share. Greater regulation and a surfeit of capital have also served to make new listings less compelling. Should we care though? Yes, to the extent that capital allocation in public markets is confined to more mature industries compared to newer ones in private markets. Are most investors denied the opportunity to participate in these secular changes because of this? Are conventional benchmarks a help or a hindrance? Are they truly investable or perversions of how we imagine the market to be?

Paul Wolley and Dimitri Vayanos in their seminal paper “Curse of the Benchmarks”³ highlight the constraints of benchmarks and particularly market capitalisation. The lack of effective pricing in the fundamental value of an enterprise and the momentum behaviour that goes with traditional benchmarking are clear weaknesses, they argue. Again, the misallocation of capital is the result. For active managers trying to mitigate these risks but confined by tracking error constraints, the problems persist. Taking a limited amount of off-benchmark risk may satisfy the investor’s perception of what good risk management is, but when your benchmark is hopeless anyway, it hardly matters. Today, with the increasing emphasis on societal good—whether that’s inclusion, climate change or responsible lending—the question of whether benchmarks are adequately reflecting the stewardship needs of many asset owners is a real concern.

So what should a good benchmark look like? There continue to be a number of admirable solutions for those considering benchmarks as bellwethers for the market – GDP weighted composition, equal weightings, ESG exclusions and smart beta developments have been embraced by many. But a benchmark that starts with an investment objective, not simply a reflection of market composition, has to be the better starting point. For those looking to manage external obligations (pension funds, charities etc.), the risk of an erosion of future purchasing power leads them to an inflation-plus objective. For those seeking better returns than their bank (retail investors), a cash-plus objective makes sense. Nearly all investors will be most sensitive to the risk of a permanent loss of capital rather than just the rate of change of prices in the broader market. From this point, what asset classes and how those asset classes behave compared to each other should form the next decision.

Benchmarking has become a tyranny for many in our industry in the same way that guessing the weight of the ox became a distraction in Surowiecki’s famous book. It may be no co-incidence that we apply livestock terminology to the “herding” behaviour of many investors, stuck with poor benchmarks to follow and sub-optimal constraints to adhere to. One hopes that unlike the poor ox, we do a better job of recognising this behaviour and prepare accordingly.

Kevin Corrigan

¹Victor Lin “It’s Closing Time” Credit Suisse Trading Strategy (2017)

²Michael Mauboussin, Dan Callahan, Darius Majd “The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks” Credit Suisse Global Financial Strategies (2017)

³Paul Woolley, Dimitri Vayanos “Curse of the Benchmarks” LSE (2016)

Thank you for reading and don’t forget to comment, share and contact us for questions!